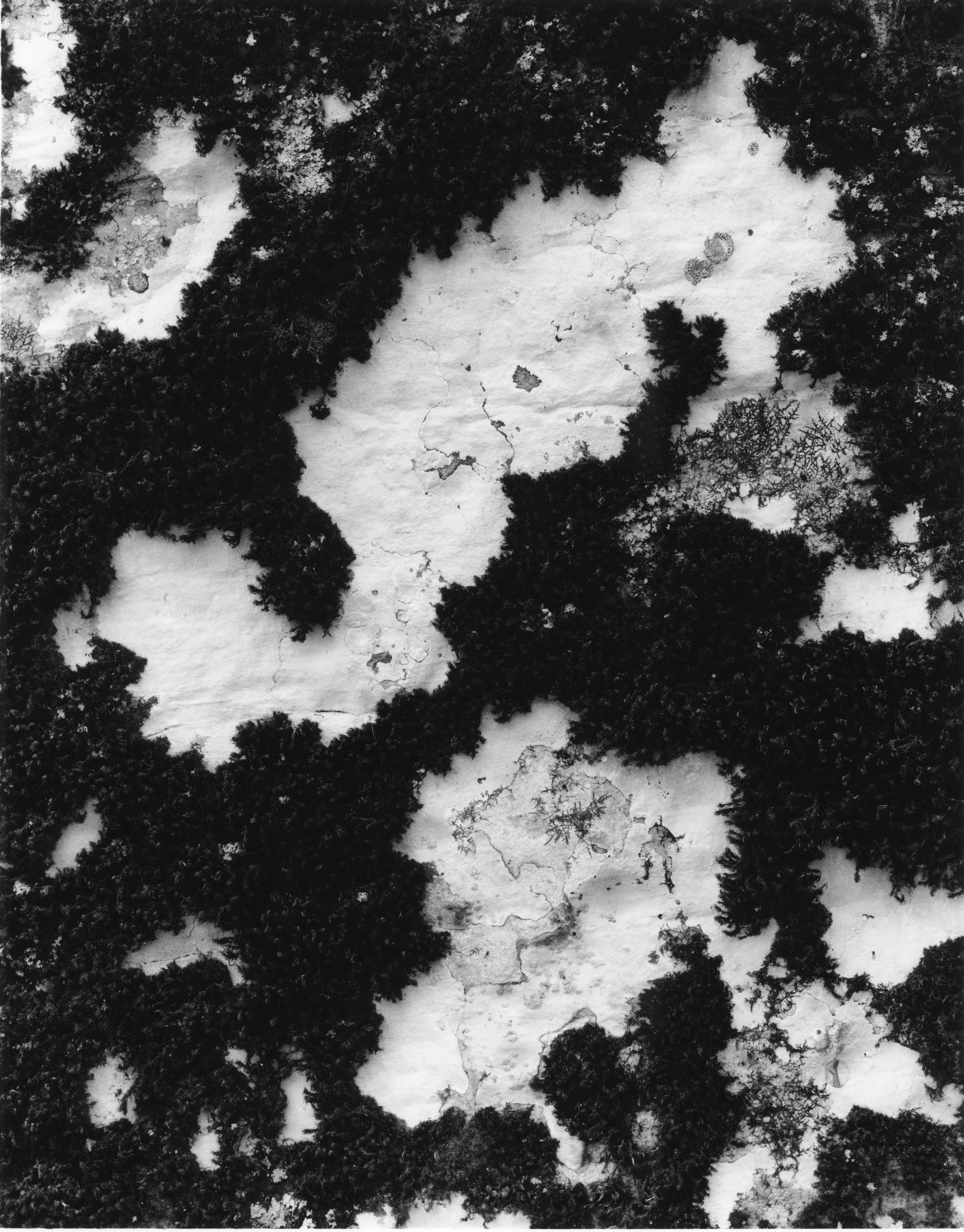

Fahan Beehive Hut, Dingle Peninsula, County Kerry, Ireland, 2001.

Of all the things I learned as the photography artist-in-residence at The Bascom Center for Visual Arts in the mountains of western North Carolina, this seems the most important: before you do anything, find your why.

It was Billy Love, the Bascom’s Deputy Executive Director for Missions and Programs, who instructed me in this idea over dinner at the Ugly Dog pub in the village of Highlands toward the end of my stay. My questions, understandably, had been this: what do I need to do next as an artist in the field of photography? What kinds of grants are available? Where should I look to show my art? All these, I know, are cart-before-the-horse questions.

The first thing to ask myself, he assured me, was why I was doing what I was doing. Why landscape photography? for example. What is my purpose? What am I trying to say? Why, in short, am I photographing rocks and rivers? The articulation of that why, as part of the residency, came in the form of the “artist statement,” a concise intonation of the purpose behind the photographs I exhibited, why I did things this way rather than how. This is of particular interest to viewers of the exhibit and, consequently, people who purchase the photographs.

He assured me that people don’t buy photographs; rather, they buy me, my story. This isn’t too different from a series of webinars I’d seen earlier in the year given by Mindy Sink, who, like me, is an author at Adventure Keen, part of Menasha Ridge Press, where I published my Hiking Kentucky’s Red River Gorge and she, for her part, published several hiking guidebooks. She insisted that people want to support you. Having a presence on social media, for example, gets people interested in your story, certainly, but more than that, they want to see you succeed. I took this to heart—especially now that I’m traveling about, promoting my Red River Gorge guide in the region.

Don’t chase money, Billy told me; instead, articulate a mission. Rather than blindly applying for grants and residencies and fellowships, and spending money to submit photographs for a curator’s consideration, instead focus on the deeper purpose and then, once it is articulated, it will be far easier to find the organizations that support the same mission as I do. They will want to help and, as Mindy said, see me succeed.

I took this to heart when I returned to Kentucky and immediately reached out to the Bernheim Research Forest and Arboretum south of Louisville. Without belaboring the point, they are involved in a legal dispute over a proposed natural gas pipeline that LG&E wants to route through this forest—home to, in some cases, federally endangered species, not to mention some of the region’s most notable flora and animals. I reached out, too, to our local chapter of the Sierra Club and another organization, Save Bernheim Now, both of which are trying to halt the pipeline process. My own proposal was simple: to go into the conservation easement that the utility giant wants to use and document—in words and on film—the place itself, what is at stake.

In doing so, I am addressing one of my most important “why’s”: my passion for conservation. My desire to see Kentucky developing resources other than fossil fuels. To learn more about the natural landscape, historic and contemporary, of Kentucky. As you might expect, all the organizations involved—with the exception of LG&E, no doubt—are interested in what I am proposing and willing to help. Anything helps, they say.

Today, as well, thinking about the rising anxieties over artificial intelligence, AI, especially as it will invariably affect (and already has) both artists and writers—the core of my own identity and, frankly, my own economy and employment—I began to write about it. And as I’ve suggested in other blogs, I myself played out the argument that relying on AI to be creative will cost us a sense of “meaning,” all the while I myself wrote in a state of “flow,” all semblances of my self lost, profoundly motivated—to put it simply, I found “meaning.” Not only found it but lived it.

And here’s the point: when I engage with my “why,” I am motivated. I feel the surge of energy that presses me on, keeps me interested and fascinated, drives me to create something that will help. I can help other people—the organizations involved in the fight, the lives of animals and trees at stake, and most importantly, the people who may not yet realize what is happening at the edges of the forest, the edges of the economy, the frontiers of society and the footnotes of the news. I can help people discover the magic of a place, delineate its value, fight for its conservation.

If you want to find meaning, ask yourself these three questions that Viktor Frankl, the author of Man’s Search for Meaning, would certainly have extolled: What am I doing for other people? What am I adding to the tradition I practice and work within? How am I bearing my own grief, suffering, and troubles so that I may be a light to others?

The answer, then, is the meaning of your life. Find your why, and you’ll find your way.