A work of art is an act of redemption.

For some time now, I have thought about the idea of redemption. To my mind, I define the concept in as simple terms as I can find: redemption is an act of recovery.

In the past few years, I have lived through several disasters: divorce, the death of both my parents, being laid off from my job of some six years, a global pandemic. Such experiences can quickly reduce one’s life to ruins, or to a wreck at the ocean’s bottom. But what is one to do?

In 2017, I turned to photography. Rather, I turned back to photography, as I’d never really stopped taking photos, though I’d long since stopped making photographs on film. I took my father’s Pentax K1000 from the closet, and I began shooting in earnest. This was, of course, the first act of redemption.

What I’d done was to recover what was of value of my father, and in this case it was the camera he gave me, but it was also the love of creativity that I shared with the man who was, for much of his life, an engineer or a professor of engineering.

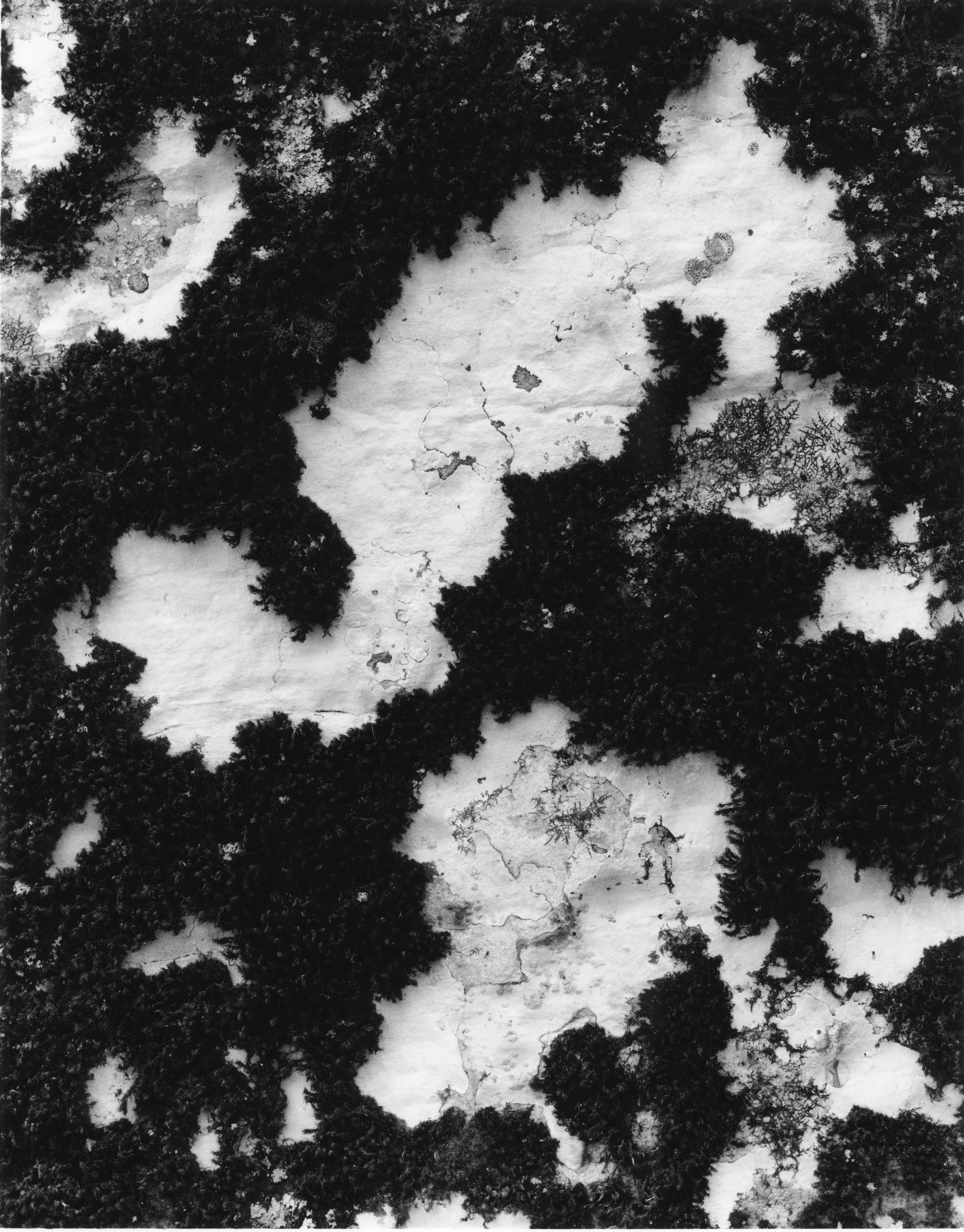

By 2018, I’d purchased my first large format camera and built myself a darkroom. This image, a print of patches of moss on a colossal boulder of sandstone, was taken just above the Rockcastle River in southeastern Kentucky, in the Appalachians. It, too, is an act of redemption, but of a different order.

It is, to me, redemptive in the sense that it is an act of recovering from that day the gold that lies in the experience. I had traveled to this property, a wilderness demonstration site owned by the group Appalachian Science in the Public Interest to meet the caretakers, a couple, both former Buddhist monks at the Furnace Mountain Zen Center in the mountains above the Red River. I wanted to see how they lived. Gretchen Lee Collins, whom I’d followed on social media for a few years, often posted inspiring poems, words, and photographs. It was she who showed me around the trails—her partner, Martin Mudd, left after I met him to do some woodcutting work, if I remember right—and this trail, crossing over a few dry washes, was one.

A photograph is an impression. I think of Edward Weston when I say this. Gretchen, who was doing work around their living space, left me to my own devices. I settled into the draw and looked, listened. It was late October, many colored leaves still on the trees. The quiet was punctuated only by an occasional wind. I found what I would guess to be an old logging road and followed it up to this boulder—”house-sized,” as is often said.

My eye settled on the shapes, the negative impressions left in the moss. They made me think, naturally, of Brett Weston and of Minor White. “Be still with yourself,” White had said, “until the object of your attention affirms your presence.” I set up the view camera, stretching the bellows around 1/3 of a stop past infinity, and shot this wall several times.

It is enough to have left the place with a single negative. I had spent the morning shooting, too, along some cliffs above the road with my Pentax 6x7. But it was this negative that redeemed the experience, where the value of the day was released from the investment I had made—the traveling, the expenditure of fuel, the time. Had I walked out with nothing, I could have likely been satisfied. Often I am, but this time I gathered something. I figured I was like Jason with the Golden Fleece, all the journey made more valuable because I’d found the treasure that I could take back to the village, to friends.

As I was printing this, I had one such person in mind. When I’d posted a scan of the negative on social media, one friend, Megan Falce, whom I’d met out at the Pine Mountain Settlement School years before, loved it. My response was instantaneous, and I resolved to make a print for her. I have by now done so. It makes me happy to do so; she enjoyed it, so why not offer it to her? Isn’t this why we photograph? To share? To explain the value of a place, a time, a moment?

Redemption is to cull the merit of such a moment. It is to make a negative from a day spent in the mountains. It is to perfect a negative from fifteen minutes spent in the darkroom. It is, finally, to make art from days spent at the enlarger, from washing and toning and drying prints before cutting matboard, framing them, mailing them to a post office box in a far reach of Kentucky.

The redemption of art is what affords us the reward: the pleasure that not only I take, but that a viewer takes, be that viewer a friend or stranger. I work toward such achievement.